Student Efforts Sparked Change

A look at 50 years of ethnic studies at Cal Poly

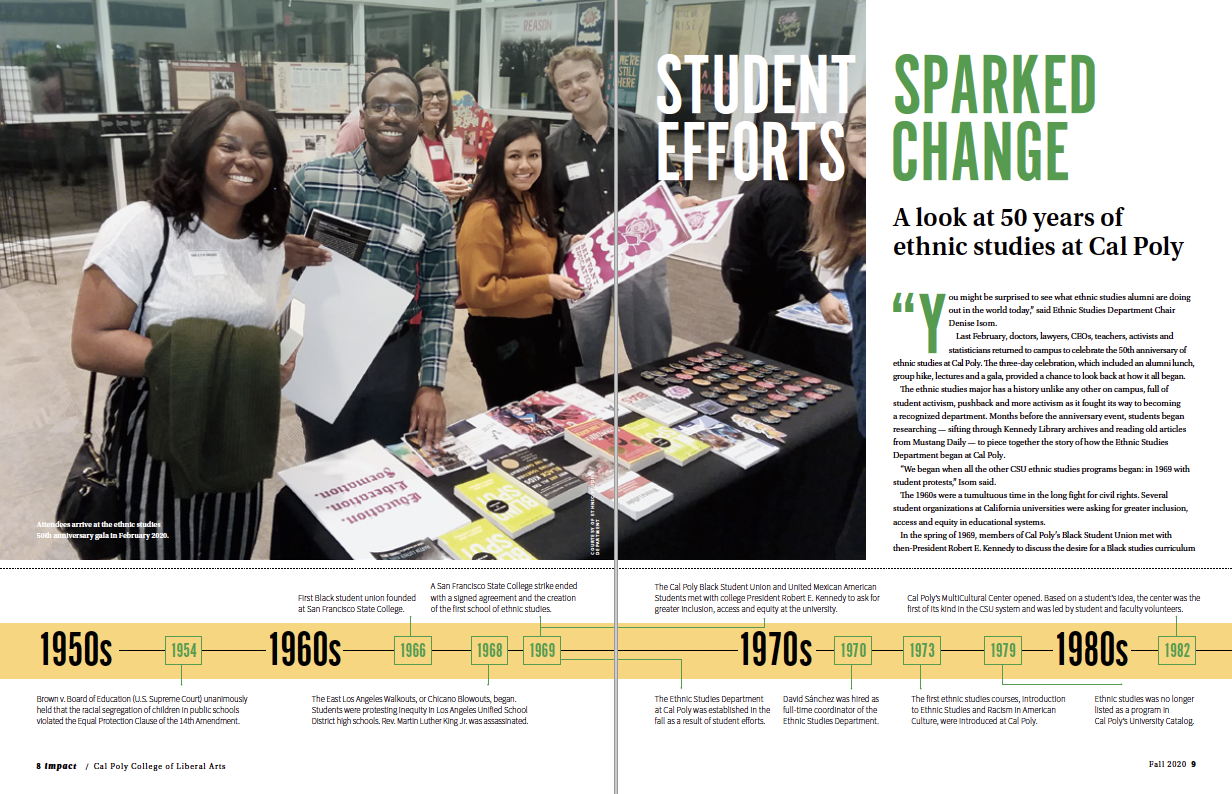

Attendees arrive at the ethnic studies

50th anniversary gala in February 2020.

Black students at Cal Poly voluntarily

taught off-book ethnic studies classes in 1968

Cal Poly students after a march in 2018.

Attendees take part in a screen-printing station

during the anniversary celebration.

Ethnic Studies Department faculty, staff and

students enjoy graduation in 2012.

You might be surprised to see what ethnic studies alumni are doing out in the world today,” said Ethnic Studies Department Chair Denise Isom.

Last February, doctors, lawyers, CEOs, teachers, activists and statisticians returned to campus to celebrate the 50th anniversary of ethnic studies at Cal Poly. The three-day celebration, which included an alumni lunch, group hike, lectures and a gala, provided a chance to look back at how it all began.

The ethnic studies major has a history unlike any other on campus, full of student activism, pushback and more activism as it fought its way to becoming a recognized department. Months before the anniversary event, students began researching — sifting through Kennedy Library archives and reading old articles from Mustang Daily — to piece together the story of how the Ethnic Studies Department began at Cal Poly.

“We began when all the other CSU ethnic studies programs began: in 1969 with student protests,” Isom said.

The 1960s were a tumultuous time in the long fight for civil rights. Several student organizations at California universities were asking for greater inclusion, access and equity in educational systems.

In the spring of 1969, members of Cal Poly’s Black Student Union met with then-President Robert E. Kennedy to discuss the desire for a Black studies curriculum. and for more Black instructors and students. The United Mexican American Students organization also met with Kennedy to ask for more representation on campus committees and in leadership.

Those efforts sparked the fall 1969 creation of the Ethnic Studies Department at Cal Poly. Originally, courses were drawn from other departments on campus and looked nothing like the ethnic studies courses taught at Cal Poly today. Course titles included Educating the Culturally Deprived Child and Culture of the Brown American Preschool Child.

Criticism from students led to the hiring of a full-time department coordinator, David Sánchez, in 1970. The first department-specific courses, Introduction to Ethnic Studies and Racism in American Culture, were introduced in 1973.

Tony Dominguez (Social Sciences, ’79), who served as the president of what’s now known as MEXA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlán) when he was a student, said he fondly remembers the efforts of the students, who demanded a more diverse faculty pool and course selection.

“If it wasn’t for the students, there would be no ethnic studies,” Dominguez said. “Students of color were fed up. They said, ‘You know what, we’re tired. You don’t teach our histories — the histories of Indigenous people, Black people, Latinx people. We want our children to know what our struggles were in order to get to where we are today.’”

Dominguez said he may not have gotten his degree without the support he found in his ethnic studies classes at Cal Poly.

“It gave me confidence about who I was, made me feel that I was worthwhile,” he said. “When you hear about some of the things that are part of your cultural background in a four-year university, it makes you feel respected.”

Unfortunately, ethnic studies as a listed program disappeared starting with the 1979–81 University Catalog, though the courses remained. However, student activism and efforts to diversify Cal Poly continued. In May 1993, students wrote letters and led protests asking to recruit more faculty, staff and students of color; to require ethnic studies courses; and to make diversity training for Associated Students Inc. members mandatory. In January 1994, Cal Poly approved an ethnic studies minor, which first appeared in the 1994–97 catalog. In 2005, comparative ethnic studies became a major, and the department welcomed its first majors in 2006.

Today, ethnic studies courses at Cal Poly often involve working with surrounding communities. In one ongoing project, Cal Poly students collaborate with local public school teachers to develop syllabi and assessment practices to help them teach ethnic studies subjects in their classrooms. Another project seeks to uncover San Luis Obispo’s global origins. Professor Grace Yeh created the Re/Collecting Project, an online archive formed with help from students who interviewed community members to uncover untold histories of marginalized communities on the Central Coast. The department also remains a place where cultures are studied and celebrated. For example, Professor Jenell Navarro teaches Hip-Hop, Poetics and Politics, which produces the biennial Hip Hop Symposium.

“We really designed a program to maximize the possibility of exploring other interests,” Isom said. “We expect our students to double major or add minors. I think the record number of minors is five.”

This flexibility allows students to pursue a wide range of fields and bring the important perspective of ethnic studies into their respective industries. For example, Isabella Montenegro (Ethnic Studies, ’13), a nurse who attended the anniversary lunch, said she used what she learned in her ethnic studies classes to develop an Indigenous language translation center at her hospital to help patients communicate their needs with staff members.

“Now you can see a reflection of the breadth of the field of ethnic studies, its interdisciplinary nature — from science and technology to literature,” Isom said. “We want to show students everything you can do with ethnic studies. It’s as vast as film school, medical school, law school, business and human resources. You name it, and we have a student who’s engaged in it.”

Download a pdf of this article or a pdf of the full IMPACT magazine.